The executive summary stresses the importance of the U.S.

natural gas storage system and the different services and benefits it provides.

“These resources not only

help meet seasonal fluctuations and short-term surges in demand but also

provide critical backup during unplanned disruptions. Many storage facilities

are strategically co-located with baseload and peaking electricity generation sites

to enhance supply flexibility and grid reliability. Storage supports a diverse

set of market participants, including pipeline operators, local distribution

companies (LDCs), electric utilities, and independent operators, by ensuring

continuity of service and stabilizing prices in volatile market conditions.

Market participants utilize storage for supply and optionality.”

The multiple roles of natural gas storage include balancing

seasonal demand, tempering price volatility, providing emergency support, and

enabling grid flexibility and renewable integration. Gas storage operators fill

storage reservoirs in the off-season when prices are usually cheaper. They may

buy and replenish supplies when prices are low and release and sell when prices

are high. They also provide price volatility protection for consumers.

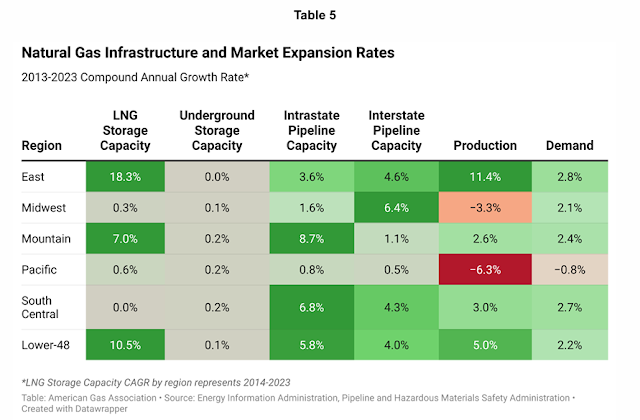

The report stresses the need

for more natural gas infrastructure, including pipelines and storage fields, in

light of increased gas production and demand growth. However, the report also

notes that “LNG storage capacity more than doubled between 2021 and 2023,

growing from 28.3 Bcf to 67.3 Bcf, largely driven by export growth and expanded

use in areas without underground infrastructure.” The need for more gas

storage is indicated by several regions exceeding 90% of underground storage

utilization.

As more natural gas is used

to power the grid, the seasonality of gas has changed to accommodate higher

summer usage to power cooling demand.

The report identifies four

areas where capacity constraints, delivery challenges, and planning gaps are

occurring: 1) Storage capacity constraints, which are common in winter but are

becoming common in summer as well. 2) Limited withdrawal rates – can cause

bottlenecks and limit optionality for storage providers. 3) Project development

timelines – permitting and regulatory red tape are a major cause, and permit

reforms are needed. 4) Market signals – they often do not reflect the full

range of gas storage value.

Recommendations include: 1)

Targeted Expansion in high-demand regions where capacity utilization averages

above 90%. 2) Faster, Clearer Project Approvals – streamlined, more efficient

permitting. 3) Improved Integration with Energy Planning – consideration of gas

storage in state and regional energy planning. 4) Recognition of the Full Value

of Gas Storage, including its value in reliability, resilience, emergency

preparedness, and consumer protection. 5) Support for Low-Carbon Pathways –

this includes storing renewable natural gas and hydrogen, including blending

hydrogen with natural gas.

Gas storage bridges the gap

between continuous natural gas production and variable demand.

The main body of the report

begins with gas storage basics, as I have written about

previously. It also addresses LNG storage. It notes some of the features of

LNG:

“The liquefaction process requires cooling the gas

molecules to around -260° Fahrenheit. The volume of LNG is about 600 times

smaller than natural gas in its gaseous state, which helps improve storage and

shipment efficiency. Today, LNG is most commonly stored at import or export

terminals, peaker plants, or satellite facilities.”

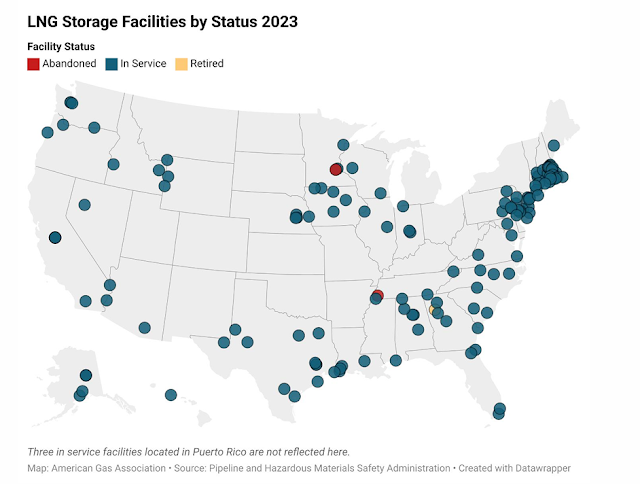

Descriptions and features of LNG storage are shown below:

Oddly, perhaps, I was just

wondering how fast natural gas moves in pipelines. The report gives an answer

below, along with some strategies for LNG storage.

“Increasingly, LNG storage can also be co-located with

electric power plants. Natural gas flows at a rate of around 20 to 30 miles per

hour, depending on linepack conditions, so co-location helps optimize pipeline

capacity and improve reliability for electricity producers and consumers of

electricity and natural gas. Pipeline capacity optimization, service

reliability, and mobile or temporary LNG facilities are important

considerations for the strategic deployment of LNG and the location of peak

shaving and satellite facilities along the gas distribution system.”

Floating Storage Units (FSUs), or Floating Storage and

Regasification Units (FSRUs) on ships, are another common form of LNG storage.

A discussion of linepack is

important as it is commonly used to prepare for demand increases

“Linepack is not a formal storage facility but an

inherent feature of natural gas pipeline systems. Gas system operators,

including local distribution companies (LDCs), can manage the amount of gas

within transmission and distribution pipelines by adjusting pressure levels.

This ability to “pack” additional natural gas molecules into the system serves

as a short-term buffer against hourly fluctuations in supply and demand.

Linepack helps enable system operators to respond to rapid intraday changes in

demand, even in instances when upstream supply may be temporarily insufficient.”

Compressed natural gas (CNG)

refers to natural gas that is compressed to less than 1 percent of its volume

at standard atmospheric pressure. CNG may be stored and used where pipelines

are unavailable or gas storage is not viable due to unsuitable geology. It is

stored in cylinders and delivered via truck.

Natural gas storage

facilities are owned and operated by interstate pipeline companies, local

distribution companies (LDCs), LNG peak shaving operators, and independent

operators, as shown below.

Regional storage, peak

capacities, and new additions by year are shown in the figures below.

The report goes on to discuss

in more detail market interactions, seasonality, reliability, resiliency,

demand and consumption, and how storage is compared to the five-year average, a

typical metric for assessing storage level adequacy. As the graph below shows,

summer withdrawals have more than doubled since 2010. Winter demand, in

comparison, has remained fairly constant.

The role of natural gas in

integration and backup support for intermittent renewables generation is often

not fully appreciated. When those resources go offline due to clouds, the loss

of wind speed, night, and less seasonal light, it is often natural gas

generation that kicks on to replace the loss. As the table below shows, the

U.S. natural gas storage system has about 144 times the energy storage capacity

and daily deliverability as pumped hydro and batteries combined.

Market-based valuation of

natural gas storage can be complex. The intrinsic

value of a project or contract results from the seasonal

difference, or spread, in natural gas prices. It is calculated by comparing the

seasonal difference between summer (injection) and winter (withdrawal) prices.

These seasonal spreads have diminished in recent years due to more natural gas

being exported and by increasing summer demand for it, due to its growing use

for electricity generation. The extrinsic

value of gas storage refers to the optionality outside of

intrinsic value that flexibility storage provides in response to market

changes. Responses to price movements, uncertainty, and volatility drive

extrinsic value.

“Thus, extrinsic value can be calculated as the

incremental value that storage owners can earn by re-optimizing withdrawals and

injections according to spot and forward price movements.”

As the loss of intrinsic value due to the decreasing

seasonal spreads has affected storage asset owners, the focus on taking

advantage of extrinsic value has grown. ‘Sell high, buy low’ is the formula for

taking advantage of extrinsic value. Price volatility, shown below, is a major

driver of extrinsic value. The authors note that the same market valuation

framework, mainly for extrinsic value, can be used for LNG storage.

Another type of value

is regulatory value, which has to do with providing desired

services for things like ensuring reliability and resiliency, sometimes

referred to as dividends. Cost-of-service ratemaking is the mechanism for

recovering this value, where the regulator allows a certain rate of return in

return for the reliability services provided.

The next section of the

report covers constraints, challenges, and future outlook. All new gas storage

facilities are capital intensive and require ongoing maintenance and monitoring

with drilling and maintaining of wells, upgrading outdated wells and equipment

for safety, and monitoring things like deliverability. The report does not

mention horizontal wells in gas storage fields. I worked on an early horizontal

well in a gas storage field in West Virginia back in 1996, the purpose of which

was to increase deliverability. LNG storage is particularly capital-intensive

since it must be maintained at very low temperatures, which is costly.

Bottlenecks in pipelines, often due to inadequate regional pipeline capacity,

can create problems for storage owners by preventing them from moving, buying,

or selling gas during ideal times for such actions. Deliverability limitations,

usually from the geology of the reservoir, can make it harder to deliver gas

when needed, decreasing potential profit. Storage capacity and capacity

utilization are the main factors when evaluating the need for additional

storage capacity. The graphs below reflect the topics discussed above.

The lack of new gas storage

developments could affect the supply-and-demand balance, resulting in increased

price volatility. The AGA’s natural gas demand outlook to 2030 is shown below.

They note that geopolitical shifts and regulatory changes

are wildcards that can affect future natural gas demand. Since FERC and the DOE

are the main permit approval agencies for gas storage and LNG projects, the

current administration will likely limit or throw out any potential regulatory

hurdles and seek to speed up project timelines, as is the goal of needed

bipartisan Congressional permit reform.

In the report’s conclusion,

the following statement highlights concerns and the need for new gas storage

facilities to be built.

“Despite its indispensable value, natural gas storage

faces significant challenges. Aging infrastructure, high capital costs,

regulatory complexity, and pipeline bottlenecks continue to constrain expansion

and optimization. Additionally, while the value of storage has evolved from a

reliance on seasonal price spreads to increased dependence on market

responsiveness, many regions in the U.S.—particularly the East, Midwest, and

Mountain—are experiencing storage capacity constraints that have not kept pace with

the rapid growth in production, demand, and pipeline infrastructure. As

electrification accelerates and data center energy needs rise, these storage

limitations could exacerbate volatility and reliability concerns.”

They also stress the need for

local and regional market analysis in evaluating where to expand storage:

“Regional and local market analyses can pinpoint where

additional storage may deliver the greatest strategic value and reveal how

market participants currently price existing assets. By comparing realized

actual market indicators, such as injection/withdrawal behaviors or storage

market rates, stakeholders can spot underserved markets, optimize capacity

deployment, and sharpen commercial strategies. These insights also equip

regulators and policymakers to target infrastructure investments and regulatory

reforms that uphold reliability and advance other goals.”

References:

Assessing

the Value of Natural Gas Storage: A Strategic Asset for Grid Reliability,

System Resilience, and Operational Flexibility in a Changing Energy Landscape. American

Gas Association. April 29, 2025. Value-of-Storage-FINAL.pdf

No comments:

Post a Comment