We humans create

significant amounts of solid waste and hazardous waste. That waste stream has

varied through time and continues to vary as technology and materials use

change. We deal with solid waste in three main ways: sanitary landfills, incineration,

and reuse/recycling. Hazardous waste may be disposed of in special landfills or

may be injected into wastewater disposal wells. Landfills also emit methane that

may be captured, used, processed into renewable natural gas, and sold. They

also produce CO2 and toxic gases. Landfills also produce toxic leachate that

can enter groundwater aquifers. There has long been a debate about whether

recycling or landfilling is better for the environment, but it is also clear

that both will continue at robust levels.

Solid waste is

classified into three types: 1) Municipal solid waste, 2) Special waste, and 3) Hazardous

waste. Municipal solid waste is basically residential and commercial trash. Special

waste may be of seven types: 1) Medical waste, 2) Construction debris, 3)

Asbestos, 4) Mining waste, 5) Agricultural waste, 6) Radioactive waste, and 7)

sewage sludge. Medical waste is dangerous to workers and the public because it contains

infectious agents. Healthcare workers have the highest exposure potential. Needles

and other ‘sharps’ are a major avenue of exposure. Transmission of Hepatitis B

and C and HIV are major concerns. Construction debris may be disposed of in special

construction materials landfills or in municipal solid waste landfills. Like

construction debris, asbestos is regulated separately. It has specific disposal

requirements to minimize airborne asbestos fibers that cause lung disease. Mining

waste volumes exceed the volume of all other solid wastes combined. Mining wastes

can be sources of acid mine drainage and heavy metals. Agricultural waste has

become more concentrated in industrial-scale farming localities.

Hazardous

waste is waste that has the potential to harm human health and ecosystem health.

The U.S. EPA Resource Conservation & Recovery Act (RCRA) has specific classifications of hazardous waste. Hazardous waste is defined in two ways. First is a listing of

about 500 types of industrial waste, often from specific processes. The way it

is defined is through EPA criteria for specific properties of the waste such as

ignitability, corrosiveness, reactivity, and toxicity. Exclusions from hazardous waste designation are given to oilfield wastewater and hazardous household

chemicals.

Waste Stream Reduction: Mainly Recycling

Waste

management strategies include waste stream reduction. Recycling and

substitution of materials and changing consumer habits are common ways to

reduce the waste stream. Recycling and circular economies can be developed for

industrial and municipal waste.

Certain types

of waste can be challenging. Used tires can be landfilled but often float

upward and cause problems. Tires stored in open dumps can breed mosquitoes and

tire fires once ignited are difficult to extinguish. The ash can leak toxins which

can be carried into surface water and groundwater. Therefore, tire recycling is

desirable. Counties and solid waste districts often handle tire recycling opportunities

for residents and businesses. Unfortunately, tire recycling, like most forms of

recycling, is often uneconomic or marginally economic. However, since waste

reduction is a clear public good, recycling programs should continue, funded by

both private and public sources.

Sanitary Landfills, Industrial, and Hazardous Waste

Landfills

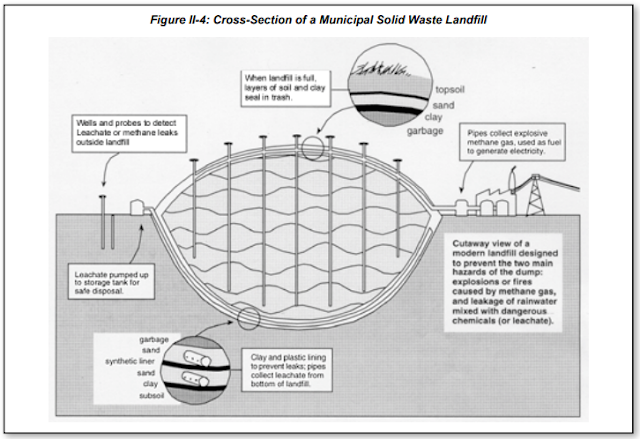

Sanitary

landfills replaced the open dumps of the past that were known for pest vectors,

noxious odors, and easily mobile contaminant potential. Landfill site selection

involves groundwater, surface water, and soil evaluation. Topography is also a

consideration. Then grading can begin. Erosion and sediment control is then

established. An under-barrier is installed to keep leachate water from

percolating down into groundwater aquifers. Landfill leachate can be quite concentrated

and toxic. Leachate collection and treatment systems are installed. Monitoring

wells may be drilled to determine if leachate has entered groundwater. Leachate

monitoring wells are drilled adjacent to cells close to the cell depth and

groundwater monitoring wells are drilled deeper into aquifers. Landfills work

by setting up waste cells. The waste is received, compacted, and covered with

soil frequently, usually daily. Industrial or hazardous waste landfills are

similar but much more heavily regulated. Often these waste streams are specific

and have specific preparation, treatment, and/or packaging requirements before

they are buried.

Waste Incineration and Waste-to-Energy

Most forms of

waste have been incinerated. Many facilities capture energy for use. These are

waste-to-energy plants. Incineration reduces the amount of waste being

processed. Completeness of combustion is a consideration at incinerators. This is ensured by the three T’s: 1) Time – how long the waste and its combustion gases

are in the burn chamber, 2) Temperature – amount of energy needed to break

molecular bonds and complete the combustion reaction, and 3) Turbulence –

agitation of solids and combustible by-products that leads to more complete

oxidation. Oxygen is added as combustion air. There are different incinerator designs

that often use multiple chambers for primary and secondary combustion.

Emissions from

incinerators can be quite toxic. Now they are more strictly regulated, requiring pollution abatement equipment such as electrostatic precipitators,

venturi scrubbers, and baghouses to capture fine particulate matter. Wet or caustic

scrubbers control acid gas. Activated carbon filtration systems began to be

installed around 20 years ago. These minimize products of incomplete combustion

(PICs) like polyacrylic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and dioxins. Heavy metals such as

mercury, cadmium, lead, and chromium are more difficult and expensive to abate.

Deep Well Injection

Some waste,

usually oil & gas brines, but also hazardous waste and radioactive waste

may be injected into deep wells into saline reservoirs. EPA has a specific

classification and specific construction and content requirements for these

wells. There are different classes for different kinds of waste.

Other Waste Treatment Technologies

Research into

waste treatment is always ongoing. Treatments such as “supercritical water

oxidation, molten metals and molten salt oxidation, glass melt and

vitrification processes, and waste-specific biological treatment systems and

composting.” Thermal desorption is used for old industrial waste.

Health Concerns from Solid and Hazardous Waste

The textbook Environmental

Health: From Global to Local, edited by Howard Frumkin (2005), of which part

of this post is a summary, gives five specific health concerns of solid and

hazardous wastes:

1.

Risks of infectious disease from poorly

managed solid waste

2.

Contamination of drinking water by

biological and chemical wastes

3.

Formation of air pollutants in landfills

4.

Emission of air pollutants from

incinerators

5.

Contamination of food by waste chemicals

that escape into the environment

Old open dumps had dangerous levels of dangerous pests

and without liners, they leaked leachate into groundwater. Modern sanitary

landfills have largely improved those issues. Chemical reactions occur in

landfills. As microbes decompose garbage and organic waste, organic acids are

produced, making metals in the waste stream more soluble. Dangerous

contaminants like volatile organic compounds (VOCs), industrial solvents, and petroleum

distillates are often found in landfills. Of course, the methane and CO2 released

from landfills contribute to climate change. The air emissions from landfills

are roughly just less than 50% methane and just less than 50% CO2 with small

amounts of other gases.

The book, from 2005, notes that 10% of hazardous waste is shipped across international borders. This must also be monitored and regulated. The Basel Convention regarding the transport of hazardous waste was ratified in May 2005 but not by the U.S. They stated that it needed to be approved by Congress in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act would have to be updated. The issue is of concern because many countries do not have adequate training and capabilities to process hazardous waste. Lead-acid battery recycling facilities are one example of a dangerous facility due to airborne lead dust pollution that has devastated children in Africa, Mexico, and other places.

Sometimes health

concerns can come from poorly managed solid waste facilities. Municipal recycling

facilities (MRFs) are susceptible to fires that can emit toxic smoke. Landfills

could have unforeseen erosion and sedimentation issues or leachate migration

issues. Natural disasters can generate significant amounts of solid waste such

as when houses and buildings are damaged. Both destruction and construction

debris are generated from the initial cleanup phase through the rebuilding

phase as shown below.

Global Waste Management Data and Trends

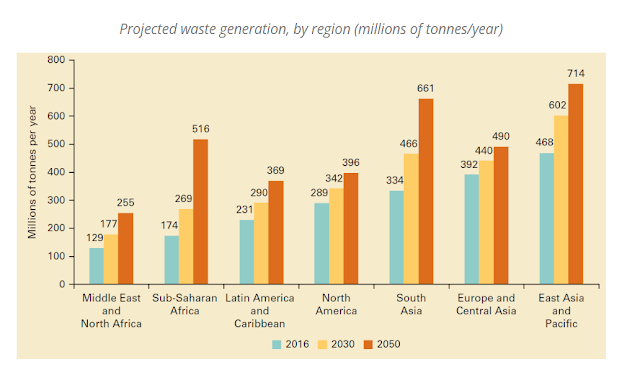

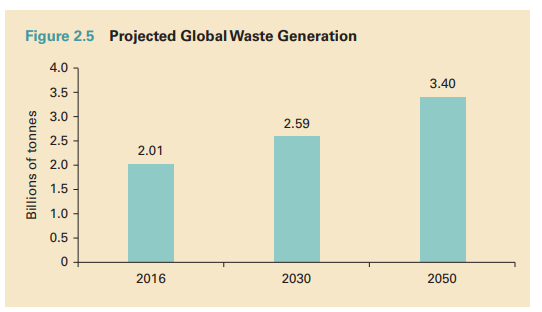

The World Bank

provides some useful global information and data on solid waste management. In

2018 they estimated that about 90% of global solid waste is either burned or disposed

of in open landfills. Open landfills and e-waste are concerning for a number of

reasons, and I plan to do a separate post about that issue. Developed wealthy

countries have better waste management systems than developing countries. Waste

management is thus a capability enabled by wealth as well as the recognition of

the importance of public health. The graphs below show some of the global waste

management data and forecasts.

EPA Rules on Solid and Hazardous Waste: RCRA, CERCLA,

EPCRA, TRI

RCRA

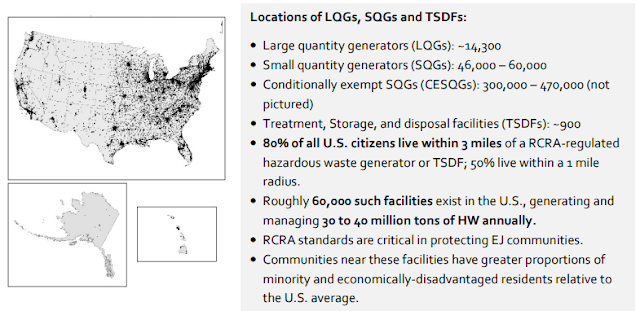

The Resource Conservation

and Recovery Act (RCRA) gives the EPA regulatory authority over solid and

hazardous waste from when it is generated to post-disposal monitoring. RCRA is

Congressionally mandated. The EPA provides guidance in the form of “explicit,

legally enforceable requirements for waste management.” RCRA has been amended

several times with required approval by the U.S. president. It was originally passed

in 1976 with amendments added in 1984, 1992, and 1996. Subtitle D deals with

non-hazardous solid waste and regulatory authority for managing it is given to

the states under EPA guidance. Subtitle C deals with hazardous waste. The EPA

may defer to states to regulate hazardous waste if the state is deemed capable.

“Subtitle C regulations set criteria for hazardous waste

generators, transporters, and treatment, storage and disposal facilities. This

includes permitting requirements, enforcement and corrective action or cleanup.”

RCRA has been amended and updated many times and continues

to evolve. The Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) rules were finalized in 2015,

for example. The amendments are shown below.

RCRA requires

groundwater monitoring around landfills. Monitoring wells are drilled into

aquifers near the landfill and the water is tested regularly. Soil vapor probes

or shallow boreholes may be drilled to test for the presence of leachate outside

the landfill boundaries. If leachate is found to be present, then corrective

actions must ensue. The ability to pay for closure and post-closure of

landfills must also be demonstrated by the owners. According to EPA:

“In order to predict whether any particular waste is

likely to leach chemicals into ground water at dangerous levels, EPA designed a

lab procedure to estimate the leaching potential of waste when disposed in a

municipal solid waste landfill. This labprocedure is known as the Toxicity

Characteristic Leaching Procedure (TCLP).”

“The TCLP

requires a generator to create a liquid leachate from its hazardous waste

samples. This leachate would be similar to the leachate generated by a landfill

containing a mixture of household and industrial wastes. Once this leachate is

created via the TCLP, the waste generator must determine whether it contains

any of 40 different toxic chemicals in amounts above the specified regulatory levels

(see Figure III-7). These regulatory levels are based on ground water modeling

studies and toxicity data that calculate the limit above which these common

toxic compounds and elements will threaten human health and the environment by contaminating

drinking water.”

Since wastes are often mixed with other waste, there is also a mixture rule that requires any amount of hazardous waste mixed with any amount of non-hazardous waste to be designated as hazardous waste. There is also the derived-from rule which covers hazardous waste residues often derived from the initial treatment of hazardous waste. These rules are described below.

RCRA also covers hazardous waste

recycling, recordkeeping, and reporting requirements. EPA’s RCRA Orientation

Manual is a useful resource for assessing RCRA compliance. Hazardous waste

transport, storage, and treatment all have RCRA requirements. Preventive

measures such as drip pads, secondary containment for tanks, leachate leak

detection, and spill response plans are required. There are specific rules for

surface impoundments, such as those that hold coal combustion residuals, or

coal ash slurry ponds. There are also air emission rules for landfills and

other waste facilities. The table below shows different technologies that may

treat hazardous waste. The second table shows the regulatory status of secondary materials

Land disposal and combustion are two ways hazardous wastes

are managed. Each has specific requirements that vary depending on the type and

composition of the waste. Permitting hazardous waste storage, treatment, and

disposal facilities has specific requirements and protocol as shown below.

Corrective

actions, or remediation, of hazardous wastes is also covered under RCRA. According

to EPA:

“Remedy implementation typically involves detailed remedy

design, remedy construction, remedy operation and maintenance, and remedy completion.

In the corrective action program, this step is often referred to as Corrective

Measures Implementation (CMI)”

Compliance monitoring

through periodic inspections and data collection and analysis are the methods

of RCRA enforcement. Below are shown the different categories of enforcement

inspections such as routine RCRA inspections, groundwater monitoring, and O&M

inspections for monitoring wells.

CERCLA

The Comprehensive

Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), commonly

known as Superfund, was enacted by Congress in 1980. CERCLA is sometimes

referred to as the hazardous waste cleanup program. While RCRA covers hazardous

waste generation, storage, treatment, and disposal, its final remediation is

covered under CERCLA. According to the EPA:

“This law created a tax on the chemical and petroleum

industries and provided broad Federal authority to respond directly to releases

or threatened releases of hazardous substances that may endanger public health

or the environment. Over five years, $1.6 billion was collected and the tax

went to a trust fund for cleaning up abandoned or uncontrolled hazardous waste

sites.”

CERCLA “established prohibitions and requirements

concerning closed and abandoned hazardous waste sites; provided for liability

of persons responsible for releases of hazardous waste at these sites; and established

a trust fund to provide for cleanup when no responsible party could be

identified.”

Two kinds of remedial action were distinguished based on priority:

short-term removals and long-term remedial response actions. CERCLA

had some amendments added in 1986. The National Contingency Plan (NCP) is a

part of CERCLA that requires planning for hazardous waste releases. CERCLA requires

site investigations to determine the best remediation technology to utilize. According

to the EPA:

“CERCLA authorizes cleanup responses whenever there is a

release, or a substantial threat of a release, of a hazardous substance, a

pollutant, or a contaminant, that presents an imminent and substantial danger

to human health or the environment.”

EPCRA and TRI

The Emergency

Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (EPCRA) was passed by Congress in 1986

to deal with hazardous waste releases into the environment. It requires

planning for the accidental release of toxic materials, or contaminants. It

requires identifying where hazardous substances are generated, transported, and

disposed of and assessing potential risks to public health in the event of a release.

Community emergency response plans are developed.

EPCRA requires

that certain industrial facilities annually report estimates of quantities and

types of hazardous waste stored onsite, treated onsite, and released to the

environment. EPA uses this data to maintain its Toxic Release Inventory (TRI).

Waste Management Financing and Oversight: Budgets,

Cost-Recovery, and Solid Waste Districts

Waste management

at the municipal level is funded by trash removal customers and by state,

county, and local governments. EPA puts the minimum solid waste management costs

in low-income countries for collection, transportation, and disposal in

sanitary landfills at $35 per ton (2014). Adding advanced approaches like waste

treatment and recycling the costs can be $50-100 per ton or more. For cities,

solid waste management often makes up 4% to 20% of the municipal funds. Local

governments provide about half of the required investments for waste services, with

the rest typically provided through national government subsidies and the

private sector. Capex and Opex are the two main cost requirements. Capital is

required to build landfills, to buy and maintain trucks, and to buy dumpsters

and bins. Labor, fuel, and equipment maintenance costs are an important

consideration. Operational costs can be challenging and often make up 70% or

more of solid waste operating budgets. Typical costs are shown below.

Costs for incinerators and anaerobic digestors are given

below. It can be seen that incinerators are roughly comparable to landfilling

costs. “Construction and operation of anaerobic digestion and incineration

systems require a large budget and high management and technical capacity.”

The World Bank writes:

“Waste management investment costs and operational costs

are typically financed differently. Given the high costs associated with

infrastructure and equipment investments, capital expenditures are typically

supported by subsidies or donations from the national government or

international donors, or through partnerships with private companies. About

half of investments in waste services globally are made by local governments,

with 20 percent subsidized by national governments, and 10–25 percent from the

private sector, depending on the service provided.”

In high-income countries, there is better solid waste

management and continuous improvement. Leachate collection systems, biogas

capture and use, and functional recycling supply chains are common. Captured

biogas may be processed into renewable natural gas.

In the U.S. many states have solid waste districts, usually at the county level or a district may encompass multiple counties. These districts are tasked with planning and management of solid waste. They collect data, develop plans, have regular meetings, produce reports, and assess fees guided by the state.

Public Participation, Input, and Opposition

As noted, the

permitting process provides for a public comment period when a facility is

undergoing the permit process. Public hearings are also a part of that process.

The public participation part of permitting is shown below.

Public opposition

can spring up when there are health concerns from the public or when new waste

is added to an existing waste facility. A recent case is where a special hazardous

waste landfill in Michigan was approved to accept low-level radioactive waste

from atomic bomb byproducts from the 1940s Manhattan Project. It is the same

landfill that accepted most of the dug-up waste from the East Palestine train

derailment. Many local residents are opposed to radioactive waste being delivered.

I think they are generally misinformed since adequately disposed of low-level radioactive

waste is unlikely to cause any problems.

Reducing So-Called Climate Pollution

EPA also helps to

fund so-called climate pollution mitigation. Although I don’t like the term climate

pollution since greenhouse gases are not like other pollutants, the mitigation path

is often similar to other air pollution mitigation. Capturing methane from

landfills is one feature. Landfills also produce CO2 which may be captured as

well but I don’t believe any landfills capture and store CO2 since it is a

smaller part of the waste stream than in combustion. Capturing the methane for

use and to mitigate greenhouse gases is important. A lesser step is flaring

methane since burning methane produces less global warming potential than

venting it. EPA’s Climate Pollution Reductions Grant Program has access to a $4.2

billion fund set aside for climate pollution mitigation. This includes methane

capture and utilization at landfills, organics recycling, clean collection

fleets, food waste reduction, processing, and composting. Facilities may apply

for the grants but may not be selected. So-called low-hanging fruit like

methane capture and leak detection and repair (LDAR) is prioritized since it

can have the biggest emissions reduction effects at the lowest cost. Oil and

gas facilities, landfills, and natural sources of methane are targeted.

References:

Environmental

Health: From Global to Local. Chapter Nineteen. Solid and Hazardous Waste. Sven

Rodenbeck, Kenneth Orloff, Harvey Rogers, and Henry Falk. Howard Frumkin,

editor. Wiley & Sons. 2005.

How

agencies in 6 states plan to spend millions from EPA climate pollution grants.

Jake Wallace. Waste Dive. August 8, 2024. How

agencies in 6 states plan to spend millions from EPA climate pollution grants |

Waste Dive

Trends

in Solid Waste Management. The World Bank. 2024. Trends

in Solid Waste Management (worldbank.org)

What a

Waste: An Updated Look into the Future of Solid Waste Management. World Bank

Group. September 20, 2018. What

a Waste: An Updated Look into the Future of Solid Waste Management

(worldbank.org)

What a

Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050. Silpa Kaza,

Lisa Yao, Perinaz Bhada-Tata, and Frank Van Woerden. With Kremena Ionkova, John

Morton, Renan Alberto Poveda, Maria Sarraf, Fuad Malkawi, A.S. Harinath, Farouk

Banna, Gyongshim An, Haruka Imoto, and Daniel Levine. World Bank Group 2018. 9781464813290.pdf

Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Laws and Regulations. U.S. EPA. 2024. Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA)

Laws and Regulations | US EPA

Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) Laws and Regulations. Final Denial of

Non-Hazardous Secondary Materials Rulemaking Petition. October 18, 2023. Final

Denial of Non-Hazardous Secondary Materials Rulemaking Petition | US EPA

Resource

Conservation and Recovery Act: Critical Mission & the Path Forward. U.S.

EPA. June 2014. RCRA's

Critical Mission and the Path Forward

RCRA

Orientation Manual 2014. U.S. EPA. RCRA

Orientation Manual: Table of Contents and Foreword (epa.gov)

Small

town erupts as landfill will process radioactive waste. Alyssa Guzman. Daily Mail.

August 20, 2024. Small

town erupts as landfill will process radioactive waste (msn.com)

Solid

Waste Management Planning. Ohio EPA. Solid

Waste Management Planning | Ohio Environmental Protection Agency

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment