This book is

older but is still considered a standard text for sanitarians, now often known

as environmental health specialists. At one time I was studying for the test

for registration as a sanitarian and this test is considered one of the best

study aids. This chapter is very generalized since it can be applied to many

different kinds of projects and developments.

Definition {of Planning}

Planning is

modeling the future using physical, social, economic, ecological, and related

factors. It involves coordination of legislative, fiscal, administrative, and

political measures in service of the model. Planning is the process through

which goals and policies are established, facts and data are gathered and

examined, different remedial or non-remedial actions are considered and

compared, and recommendations are established. Salvato notes that there is a

great need for regional planning. That is often difficult due to competing

economic, social, and environmental goals. He cautions that realistic goals

must be set. Regional planning should integrate local planning as well as

national planning. Often the end result is local implementation of regional

planning.

Environmental, Engineering, Planning, and Site

Selection Factors

Salvato gives twelve

of these factors:

1)

Geology – this usually refers to the adequacy of

the substrate for the foundations of buildings.

2)

Drainage and Flooding – this is simply avoiding

building on a floodway or flood plain.

3)

Transportation – considers the effects of

building access roads and the potential pollution effects of increased transportation

such as air pollution, dust, and noise.

4)

Aesthetics – refres to things like landscaping

and post-construction remediation.

5)

Noise Control – considers areas where noise

would be a nuisance.

6)

Water Supply – considers all water uses and potential

water impacts related to a project.

7)

Wastewater Disposal – this includes construction

and industrial wastewater as well as wastewater from sewage treatment and gray

water.

8)

Solid Waste Disposal – this includes combustion

ash residues, non-incinerable solid waste, sewage treatment sludge, and sanitary

landfill waste. All of this must be monitored for mobility into surface water

and groundwater.

9)

Air Pollution Control – Clean Air Act permitting

and compliance

10)

Occupational Health – the health and safety of workers

must be ensured.

11)

Vermin Control – insects and mammals that can

cause diseases and other problems must be limited.

12)

Environmental Impact on Surrounding Area –

compliance with all environmental laws that a project may come up against.

Any project

must face multiple compliance issues with multiple laws and statutes. Each must

be addressed, often with multiple federal, state, and local agency involvement.

Project

planning often begins with preliminary or feasibility studies. These may

include architectural and engineering reports and plans, contract drawings, and

project specifications.

Comprehensive Community Planning

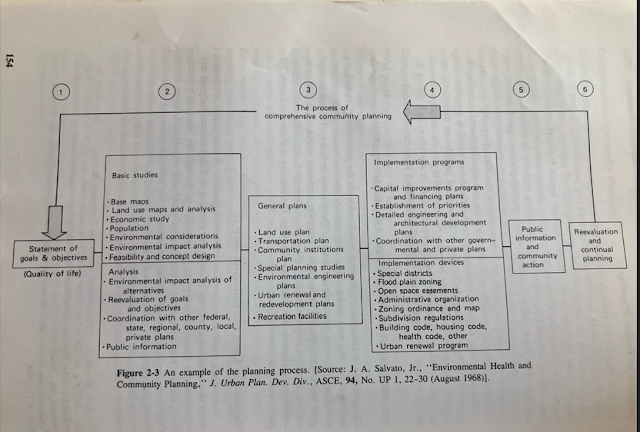

Comprehensive community planning involves consideration of social, environmental, physical, and political factors. The process can be divided into six steps: 1) statement of goals and objectives, 2) basic studies, mapping, and data analysis, 3) plan preparation, 4) plan implementation, 5) public information and community action, and 6) reevaluation and continual planning. A statement of goals and objectives considers community aspirations, environmental quality, and quality of life, as well as the factors mentioned above.

Basic studies,

mapping, and data analysis involve research and problem identification. Mapping,

land-use analysis, population & demographics, economics, transportation

systems, community institutions, environmental health and engineering

considerations, environmental impact assessment, cost-benefit analysis, coordination

with other planning, public information, infrastructure, feasibility studies,

and continual reevaluation of goals all make up a part of this vital section of

community planning.

Plan preparation

involves generating plans for the parts of step 2 mentioned in the above

paragraph including land-use plans, transportation plans, community institution

plans, special planning studies, environmental engineering plans, and urban

renewal and redevelopment plans.

Plan

implementation involves construction and along with it, problem correction,

prevention, and control. Financial plans, detailed engineering and

architectural plans, consideration of regulations, laws, codes, and ordinances,

and administrative organizations are involved in this step.

Public

administration and community action involve fostering public participation and

input. Keeping the public informed and responding to citizen concerns and ideas

are features of this step. If this step is done well, public support of the

project is likely to grow.

Reevaluation

and continual planning involve keeping everything and everyone current on the

progress of the project and any changes that occur.

“There is an urgent need for more engineering in community

planning and more comprehensive planning in engineering, with emphasis on

area-wide, metropolitan, and regional approaches. The environmental health,

sanitation, protection, and engineering factors that are essential for community

survival and growth, and the environmental, economic, and social effects of any

proposed projects must not be overlooked in planning and engineering.”

“Comprehensive community planning that gives proper

attention to the environmental health considerations, followed by phased detail

planning and capital budgeting, is one of the most important functions a

community can engage in for the immediate long-term economy and benefit of its

people.”

Regional Planning

Regional plans

are very prudent and should be comprehensive, taking into account all the

factors mentioned previously. Salvato covers the content of a regional planning report. He gives examples of a comprehensive solid waste project

study, two comprehensive wastewater project studies, and a comprehensive

environmental engineering and health planning project study.

Project Financing

Salvato also

covers project financing, particularly for municipalities. Small projects may

be financed by special tax levies or user service charges. A combination of

revenue bonding and general observation bonding is also common. Municipalities often

have limits on how much debt they can take on, usually 5 to 10% with operating

expenses at 2%. Mortgage bonds with physical utility assets as collateral are common.

Revenue bonds are repaid by sources of municipal revenue. These are not backed by municipal credit so interest rates may be higher. General obligation bonds are backed by a municipality’s tax revenue fund through additions to residents’ property taxes. These bonds have lower interest rates. There are debt limits to this type of bonding as well. Ongoing operation and maintenance also need to be considered. A combination of revenue and general obligation bonds is also common where revenue is used to pay off principal and interest and tax funds are used to cover any shortfalls. These also get lower interest rates. Ad valorum taxes on services provided such as metered water can be based on property tax assessments. In this arrangement, people with higher-value properties pay more than those with lower-value properties, for the same service. Notes are short-term loans, typically for a year or less, to cover any shortcomings. Privatization involves contracting and paying a private organization to cover the financing, subject to terms and conditions deemed in the public interest. State and federal revolving loan funds are another low-interest financing mechanism that municipalities may use to construct, repair, or upgrade facilities. Alternative financing mechanisms include bond banks, water banks, industrial development bonds, capital reserves, state corporations, lease purchase agreements, cost sharing with developers or users, private activity bonds, and federal and state government loans and grants. Grants and planning assistance from the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), the USDA, or HUD may be available. When I worked for a county health department it was funded mainly by tax levies, fees for permits and inspections (a portion of which went to the state), and a few other funds and grants.

Environmental Factors in Site Selection and

Planning

This chapter

is quite generalized so the following environmental factors in site selection

and planning are generalized as well. They include seeking sites with desirable

features; topography and site surveys; geology, soil, and drainage; utilities;

meteorology; location; resources; animal and plant life; improvements needed;

and site planning.

Environmental Assessment

“An

environmental assessment may be conducted for different purposes. It may

emphasize compliance with existing regulations and permit requirements, respond

to a spill, or relate to the potential, or existing, environmental risks and liabilities

associated with the purchase or acquisition of a property.”

An environmental audit determines compliance with

regulatory requirements. An environmental property assessment determines

potential risks and hazards associated with that particular property. Old and

new land deeds, zoning maps and codes, topographic maps and aerial surveys, historical

records, insurance history, fire department files, university reports, regulatory

agency records, and more may be consulted in environmental assessments. Past

land use, both surface and subsurface, needs to be determined. Engineers, land

surveyors, geologists, hydrogeologists, archaeologists, geographers, chemists,

biologists, attorneys, health inspectors, toxicologists, and other professionals

may be involved. Environmental assessments are advised for the purchase of real

estate, especially for commercial and municipal projects. Consultants involved

in assessments need to be aware of legal liabilities and the limitations of

assessments.

Environmental Impact Analysis

Environmental

impact analysis considers the wider regional impacts of projects. A good

regional plan with environmental, engineering, and health data and considerations

precedes the environmental impact analysis that generally has a wider regional

scope.

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA)

and the Environmental Impact Statement

Environmental

impact analysis is the main goal of NEPA. Title I of NEPA requires an environmental

impact statement (EIS) for projects deemed to have potential environmental impacts,

The statement must include a detailed description of potential impacts and provide

possible alternatives to the proposed actions. Federal agencies must be

consulted and provide guidance. It is the signoffs of multiple federal agencies

that often slow down NEPA reviews and increase timeframes for the completion of

EISs. Title II of NEPA establishes the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) which

provides an annual report to Congress. Recent permit reform proposals seek to

limit the amount of time for NEPA reviews and EISs. This is reasonable as some

of these reviews and statements can take years. This is often due to the signoffs

required from multiple agencies, several of which may be understaffed relative

to the amount of time-sensitive work needed.

The use of categorical

exclusions can help expedite reviews. These refer to “a category of

actions which do not individually or cumulatively have a significant effect on

the human environment and which have been found to have no effect in procedures

adopted by a Federal agency in implementation of these regulations and for

which, therefore, neither an environmental assessment nor an environmental impact

statement is required.” Categorical exclusions should be expanded, permit

reformers argue, to avoid unnecessary duplication of reviews resulting in EISs.

NEPA requires a

description of present conditions, a description of alternative actions, a

description of probable impacts of each alternative (including beneficial

impacts), an identification of the alternative chosen and the evaluation that led

to that choice, a detailed description of the probable impacts of the proposed

action, and a description of techniques for minimizing harm.

There is a

recommended format for EISs:

(a)

Cover sheet.

(b)

Summary.

(c)

Table of Contents.

(d)

Purpose of and Need for Action.

(e)

Alternatives Including Proposed Action.

(f)

Affected Environment.

(g)

Environmental Consequences.

(h)

List of Preparers.

(i)

List of Agencies, Organizations, and Persons to Receive

the EIS.

(j)

Index.

(k)

Appendices (if any).

Salvato gives

a more detailed EIS format description based on the 1975 Handbook for

Environmental Impact Analysis. The EIS is the end product of NEPA reviews. EIS

guidelines are given by the CEQ. A draft EIS is first prepared and circulated for

comment. After the comment period, the comments are considered and integrated with

the EIS, if warranted. A generic EIS (GEIS) is recommended during the project feasibility

analysis. This is a generalized statement. The EIS is meant to be very

comprehensive. According to Section 8(c) of NEPA:

“Each {EIS} should be prepared in accordance with the precept

in section 102(2)(A) of the Act that all agencies of the Federal Government “utilize

a systematic, interdisciplinary approach which will ensure the integrated use

of the natural and social sciences and the environmental design arts in planning

and decisionmaking which may have an impact on man’s environment.”

Salvato gives examples of EIS formats. One he gives for landfill disposal of solid wastes includes scope, definitions, site selection, design, leachate control, gas control, runoff control, operation, monitoring of gas and leachate, and a summary. He also gives lists of the aspects and disciplines that should be consulted for different kinds of projects. These include social components and physical components. Social components include services, safety, physiological well-being, sense of community, psychological well-being, historical value, and visual quality. Historic value is one that seems to often come up in NEPA reviews where historical buildings, properties, and archaeological sites are considered. Physical components include geology, soils, special features, water, biota, climate and air, and energy. Environmental impact is often not easy to estimate so there may be differences of opinion about EISs.

Salvato

mentions Geological Circular 645 by Leopold et al., (1971) as a guide to determining

potential environmental impacts. This can function as a guide to EISs. It

includes a matrix that calls for value judgments (numerical 1 to 10) relating

to environmental impact which includes magnitude and importance. The matrix includes

100 proposed actions and 88 environmental characteristics, conditions, or

categories. Even so, it is not considered to be comprehensive.

Another EIS method

divides environmental attributes into four categories: physical/chemical

(water, air, land, noise), ecological (species and populations, habitats and

communities, ecosystems), aesthetic (land, biota, air, water, man-made objects,

composition), and social (individual environmental interests, individual

well-being, social interaction, community well-being). Salvato gives examples

from the Environmental Quality Handbook for Environmental Impact Analysis that

gives environmental impact categories on a matrix from 1 to 5 from least to

most impact.

Housing and Development in Suburbia and Rural

Development

Salvato also

gives a section on housing, suburban development, subdivisions, and environmental

health considerations. These are likely reflected in the trends of the time

when these were being built up. In this analysis, he notes the need for

facilities and services that arise with new housing and commercial development.

These include solid waste disposal, recreation, sewage treatment, schools, police,

fire departments, public employees, air pollution control, street paving and

maintenance, hospital and nursing home capacity, libraries, and commercial and

retail establishments. Fiscal impacts are also considered. Agreements for costs

of services must be considered and may include impact fees in addition to

taxation. Tax revenue may include property taxes, school taxes, fire protection

taxes, sales taxes, income taxes, property transfer and other legal fees,

business taxes, transient occupancy taxes, interest earnings, permit or license

fees, and user charges for recreation, health, water, sewerage, solid waste,

and other property services. Other sources of revenue include state and federal

grants, which may be substantial. Cities and towns have developed zoning

regulations to better control development and growth. Exceeding available water

and sewage capabilities and school capacity are examples of what is sought to

be avoided by these regs.

Causes and Prevention of Haphazard Development and

Subdivision Planning

This section

focuses on fringe and rural area sanitation, especially sewage treatment

issues. Poor site selection is one reason these developments can be problematic.

Many subdivisions and rural developments have been poorly planned in the past

and are now difficult to bring up to standards and regulate. Some may be built

in flood-prone areas, in areas with poorly draining clay soils, steep slopes, and

shallow bedrock. These may result in overflowing septic systems and

contaminated water wells.

He notes that comprehensive

land-use planning and effective regulation are keys to preventing such

situations. The regulatory aspects include getting approved permits to build

from the local building department or the state, getting approved septic system

permits, designs, and final inspections from the local or county health

department, and approving drilling permits and testing private water wells for

coliform bacteria and other contaminants. Some places have specific laws regarding

subdivision development. Tapping into existing public water and public sewage

treatment systems, if possible, is desirable over-relying on individual water

wells and septic systems.

Ideally, subdivision

planning would proceed along a certain sequence of development. Land-use

planning is followed by improvement in roads, water supply, drainage, sewers,

and other utilities, and solid waste disposal. Site selection is very important

for subdivision development, especially for sewage treatment. For subdivisions

within or adjacent to a city or municipality, they would likely have regulatory

authority. For areas outside the city, the county, usually the county health

department has authority for sewage treatment, sometimes for building permits,

and water well approval and inspection.

Water systems

for subdivisions and rural communities are an issue. Individual wells may be drilled,

or multi-household wells may be shared if natural water flow rates, also known as sustainable yields, if the wells will allow it. Shallow wells that are continually

disinfected with chlorine are another option. Slow sand filtration of surface

water with chlorine disinfection may be an option.

For sewage

treatment, a centralized sewer system piped into a new sewage treatment plant may

be an option. Although upfront costs may be higher, this option can have many

advantages, including smaller lot sizes since a household sewage treatment system

(septic system) usually requires more land, especially as requirements for a

replacement system area, should the original system fail, have become more

common. The subdivision sewage treatment plant may consist of aerobic treatment

units, dosing tanks, open or covered sand filters, a chlorine contact tank,

settling tanks, recirculating filters, and other components.

Some rural subdivisions

may utilize individual household septic systems. This requires more land for a

replacement system, should they be needed. I know of a gated community around a

lake in Southeastern Ohio which I was partially responsible for regulating that

was first built long ago with each dwelling having its own well and septic

system. The area around the lake consists of steep slopes where houses and cabins

have been built. Failing septic systems are common enough in the community that

one can often smell sewage when driving through with a window down. Room for

replacement systems was not considered in the past but is required now. There

is still considerable new building going on in the community. Older failing

systems without adequate replacement areas are grandfathered in so that a new

system nay be built but must be aerobically treated, and sometimes chlorinated

and disinfected with UV lights. These are regulated under the EPA’s NPDES

program and must be sampled once a year. These samples often still exceed

contaminant levels. For several reasons, I would never want to live there,

although apparently many people do.

No comments:

Post a Comment