Wikipedia via the

WHO and other researchers like Kirk R. Smith, defines environmental risk

transition as “the process by which traditional communities with associated

environmental health issues become more economically developed and experience

new health issues. In traditional or economically undeveloped regions, humans

often suffer and die from infectious diseases or of malnutrition due to poor

food, water, and air quality. As economic development occurs, these

environmental issues are reduced or solved, and others begin to arise. There is

a shift in the character of these environmental changes, and as a result, a

shift in causes of death and disease.”

Risk Transition Frameworks

There are several

risk transition frameworks. The earliest to be used is the demographic

transition which was used in the 1940’s. The epidemiological transition

framework was utilized beginning in 1970. According to Wikipedia: “In 1990,

environmental health researcher Kirk R. Smith at the University of California,

Berkeley proposed the "risk transition" framework in relation to the

established demographic and epidemiological transition frameworks. This theory

was based on the concept that there must be a shift in risk factors leading up

to a shift in causes of death and disease. In efforts to prevent, rather than

respond to diseases, the risk transition was further studied and quantified.

Figure 1 shows the relationship between risk, epidemiological, and demographic

transition, in which risk factors change to affect patterns of disease and

health, which in turn affects the demographic. However, a shift in population

also impacts the risk factors, and so these three frameworks all show

significant impact on one another.”

Source of above graphs: Wikipedia

I first came

across the idea of environmental protection as a higher-order public good when

I read Nordhaus and Shellenberger’s 2007 book Breakthrough in the early

2010s. There, they presented environmental protection as a higher-level need

on Maslow’s pyramid or hierarchy of needs. Survival-level needs lower on the

pyramid are prioritized by people with very little discretionary cash. As we

have seen, clean energy choices are more available to those with discretionary

cash. Things like tax credits for things like rooftop solar and EVs that can be

redeemed at tax time are taken advantage of by those with the financial means

to do so. Thus, those with wealth have been able to take advantage of most of

the clean energy incentives for citizens. That means it was and is a benefit

that favors the wealthy much more than the poor. However, some of the newer

incentives such as those for new and used EVs can be applied immediately to

downpayments which makes those incentives more available to those of lesser

economic means.

Wealth is an

enabler of environmental protection. When our lower needs are met, we can approach

higher orders of utilitarian goods such as environmental protection. Environmental

protection is also viewed by many as a duty. One might fulfill that duty by

being optimally educated, and understanding the issues and the science behind them.

Another way

environmental risk transition has been described is as follows:

• This term

characterizes changes in environmental risks that happen as a consequence of

economic development in the less developed regions of the world.

• Before

transition occurs: poor food, air, and water quality

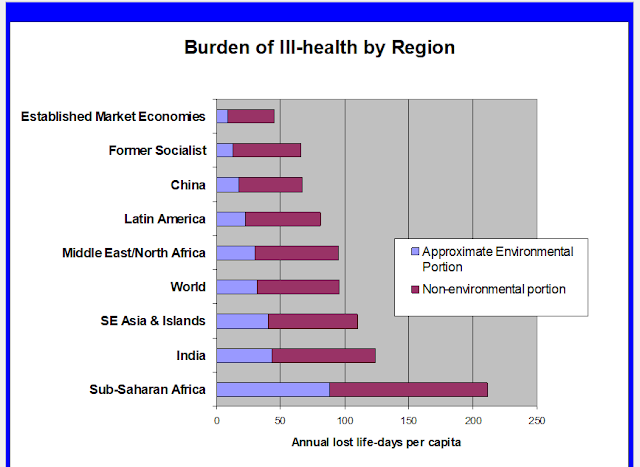

The environmental risk transition precedes the epidemiologic and demographic transitions. This means that environmental risk precedes epidemiologic and demographic risks since it is much higher in the form of the more dangerous traditional risks vs. modern risks. Traditional risks are more oriented to survival than modern risks. The graphs show a trend of traditional risks transitioning downward while modern risks begin to rise. The areas of the graphs where the two risk types converge are known as risk overlap. This is where risks transition into new forms: risk genesis. This is also where risks can be transferred when attempts to control one type of risk can increase risks of other types. This is known as risk transfer. Here, risk synergism can also occur where one type of risk changes sensitivity to other risks. The graphs below are form a power point presentation I found at a Health Dept. I work for. I am not sure of the origin.

Wealth helps

people to better mitigate natural environmental hazards such as contagious

infections and parasites, dust, dampness, woodsmoke, pollen, and other airborne

hazards, injuries from falls, fires, and animals, and heat, cold, rain, snow,

wind, natural disasters, and other adverse conditions. Once these natural hazards

are reduced those societies can focus more on higher-order public goods such as

environmental protection from anthropogenic hazards like pollution from power

plants and factories, greenhouse gas emissions, sanitation, remediation of

contamination, and better prevention and reduction of air, water, and soil

pollution.

Environmental Risk Transition Theory and Urban Health

Inequities

A study published

in Social Science and Medicine in May 2021 titled Adapting the environmental

risk transition theory for urban health inequities: An observational study

examining complex environmental riskscapes in seven neighborhoods in Global

North cities sought to “understand how environmental injustice, urban

renewal and green gentrification could inform the understanding of

epidemiologic risk transitions.” The graph below summarizes changing

environmental health exposures among affected urban populations.

Much of the study’s

data was provided through interviews with affected residents, which is valid

but such methods can be strongly biased due to the interviewees feeling cheated

by their exposures:

“Respondents reported renewed, complexified and

overlapping exposures leading to poor mental and physical health and to new

patterns of health inequity. Our findings point to the need for theories of

environmental and epidemiologic risk transitions to incorporate analysis of

trends 1) on a city-scale, acknowledging that segregation and patterns of

environmental injustice have created unequal conditions within cities and 2)

over a shorter and more recent time period, taking into account worsening

patterns of social inequity in cities.”

The paper

makes a recommendation to zoom in with such studies to smaller and more specific

populations over shorter time periods. The authors suggest that environmental risk

theory and epidemiological risk theory miss some of the important aspects of

environmental health, in particular the higher environmental exposures of some

populations. I do object to the term environmental racism. While there

was no doubt such activity in the past, especially in regard to environmental

justice communities being over exposed to certain risks and pollutants, I think

there is very little evidence of that happening in modern times. I still think

nearly all of these environmental justice communities are legacy communities,

exposed due to past actions that have been largely corrected. There may be a

few cases here and there, but it is mostly not an issue these days.

“Our results have important implications for

epidemiologic theory and methods. We find that studying epidemiologic risk

transitions on a finer geographical scale and over shorter timeframes than

traditional theories linking risk transitions to larger-scale development

illuminates important nuances to identifying risks that contribute to

socio-spatial health inequity in cities. Theories of epidemiologic transition

have described the evolution of causes of morbidity and mortality as

populations move through phases of development, often emphasizing the

contribution of riskscapes in urban settings as exposures are modified via

urbanization. However, the epidemiologic and environmental risk transition

frameworks fail to identify more finite patterns resulting from exposure to

persistent, transitional, new, and emerging environmental risks which are

inequitably distributed within cities inequalities due to the ongoing impact of

environmental racism (Friel et al., 2011). Failing to account for the resulting

overlapping and synergistic risk factors, as often happens using a traditional

epidemiologic approach, may lead to an underestimation of a population's true

burden of exposure and to the inability of cities to address historic and new

health injustices.”

Environmental

Kusnets Curves

In the 1950s and 1960s economist Simon Kusnets developed a hypothesis that stated that “as an economy develops, market forces first increase and then decrease economic inequality.” The original Kusnets Curve shown below, developed around 1960, was concerned with inequity and increasing wealth. It has been strongly criticized and many say invalidated due to the fact that inequality has increased in many societies since 1960 even though it had dropped through the first half of the 20th century. However, Kusnets curves such as the environmental Kusnets curves that show pollution or environmental impact vs. wealth are still considered by many to be valid models.

According to Majeti

Narasimha Vara Prasad in the 2024 book, Bioremediation and Bioeconomy:

“The

Environmental Kuznets curve suggests that economic development initially causes

deterioration in the environment. Later due to economic growth, society begins

to improve the relationship with the environment, and environmental degradation

reduces. Thus, the economic growth is good for the environment. Nevertheless,

critics are of the view that there is no guarantee that the economic growth

will lead to an improved environment—in fact, the opposite is often the case.

At the least, it requires a very targeted policy and attitudes to make sure

that economic growth is compatible with an improving environment.”

Environmental

Kusnets curves seem to be generally valid models for some pollutants, some ecological

impacts, carbon footprints, and waste products such as sewage. Decoupling of these

things from economic growth is confirmed, which is part of the curve trajectory

pattern. We are close to peak emissions, peak pollution, and peak other waste

products. Wealth is a huge factor in these successes. So too is technological improvement,

which also tracks well with wealth.

A January 2024

paper in Nature: Humanities and Social Sciences Communications by Qiang Wang,

Xiaowei Wang, Rongrong Li and Xueting Jiang, titled Reinvestigating the

environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) of carbon emissions and ecological footprint

in 147 countries: a matter of trade protectionism, aimed to validate the EKC

hypothesis, with success when the variables of economic growth, environmental

degradation/improvement, and trade protectionism are compared statistically and

graphically.

From the study’s

conclusion:

“This study conducted a comprehensive investigation

into the intricate relationship between economic growth, trade protectionism,

and environmental indicators across 147 countries, segmented into four income

groups. The utilization of the Pedroni cointegration test further validated the

existence of stable long-term correlations between carbon emissions, ecological

footprint, and other variables, establishing the groundwork for nuanced

regression analyses. Notably, the study pioneered the exploration of threshold

effects, unveiling non-linear relationships between trade, economic growth, and

environmental outcomes across income groups. The elucidation of threshold

models revealed intriguing insights, showcasing varying impacts of trade on

economic growth, carbon emissions, and ecological footprints. Particularly

noteworthy were the distinct thresholds identified across income groups,

delineating changes in the relationships between trade, economic growth, and

environmental impacts. These findings underscored the nuanced nature of

economic development’s impact on environmental degradation, supporting theories

such as the EKC within specific income brackets while uncovering divergences in

others.”

Environmental Risk Assessment, Risk Management, Risk

Perception, Risk Education and Risk Awareness

The nexus of humans

and risk is multifaceted and sometimes counterintuitive. There is often a

mismatch between real risk and perceived risk. Both human psychology and neurobiology

are at play in our interfacing with risk. Danger invites fight-flight-freeze

reactions at the amygdala level in our pre-logic emotional circuit. The

mismatch is known as the risk gap (between real and perceived risk).

Risk assessment is important as a necessary early step that precedes and supports

risk management. There are many factors that influence human risk perception

including media, media trends, news events, past events, and the different types

of risks. Some risks are misperceived due simply to lack of knowledge about

them. In these cases, the risk gap is simply a knowledge gap. A recent study

about PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), also known as forever

chemicals, found that 76% of people surveyed by Texas Water Resources Institute

knew nothing about PFAS chemicals. 41.5% of respondents had not heard of them

and 31.6% of respondents had heard of them but were unaware of the risks. 11.5%

of respondents were aware of PFAS contamination. 97.4% of respondents did not

believe their own drinking water had been affected. For several years now I

have been hearing about PFAS chemicals as emerging contaminants in

environmental circles. The results of the survey are an example of risk

awareness, in this case lack of awareness about the risks, which possibly

include cancer and reproductive problems. Research has confirmed that many

people have been exposed to PFAS chemicals. Risk education can help to increase

risk awareness. Risk misperceptions can lead to focusing resources on the wrong

variables, ones that don’t best help to solve problems.

References:

Environmental

Risk Transition. Wikipedia. Environmental risk transition -

Wikipedia

Adapting

the environmental risk transition theory for urban health inequities: An

observational study examining complex environmental riskscapes in seven

neighborhoods in Global North cities. Helen V.S. Cole, Isabelle Anguelovski,

James J.T. Connolly, Melissa García-Lamarca, Carmen Perez-del-Pulgar, Galia

Shokry, and Triguero-Mas. Social Science & Medicine. Volume 277, May 2021,

113907. Adapting the environmental risk

transition theory for urban health inequities: An observational study examining

complex environmental riskscapes in seven neighborhoods in Global North cities

- ScienceDirect

Bioremediation

and Bioeconomy: A Circular Economy Approach. Book • Second Edition • 2023. Bioremediation and Bioeconomy |

ScienceDirect

Reinvestigating

the environmental Kuznets curve (EKC) of carbon emissions and ecological

footprint in 147 countries: a matter of trade protectionism. Qiang Wang,

Xiaowei Wang, Rongrong Li & Xueting Jiang. Humanities and Social Sciences

Communications volume 11, Article number: 160 (2024) January 24, 2024. Reinvestigating the environmental

Kuznets curve (EKC) of carbon emissions and ecological footprint in 147

countries: a matter of trade protectionism | Humanities and Social Sciences

Communications (nature.com)

The

Environmental Risk Transition. Power Point Presentation. (unknown origin)

Kusnets

curve. Wikipedia. Kuznets curve - Wikipedia

Researchers

raise concerns after surveying Americans about common risks: ‘A significant

knowledge gap’. Laurelle Stelle. The Cool Down. March 17, 2024. Researchers raise concerns after

surveying Americans about common risks: ‘A significant knowledge gap’ (msn.com)

No comments:

Post a Comment