I acquire a lot of single-use polyethylene plastic bags through shopping but each one gets used to bag up used cat litter, which is then landfilled. Thus, in my case, they are used at least twice unless they have holes. The town where I do most of my shopping recently banned these plastic bags so, now I am collecting lots of paper bags. I did obtain by mail some more permanent bags and have been using them. I have to remember to bring them and/or keep some in my car. I am not sure if they are woven or non-woven, but I am guessing woven. I plan to reuse the hell out of them. I’m rather neutral on the subject of whether plastic bags should be banned or not, but I lean towards not banning them. Thus, I thought I would read some articles from internet sources and see what the experts and others say.

Fox News

recently reported on the backfiring of plastic bag bans in New Jersey. The

report was based on research by Freedonia Custom Research (FCR), a business

research division for MarketResearch.com. Fredonia Group, an affiliate, reported

that the “shift from plastic film to alternative bags resulted in a nearly

3x increase in plastic consumption for bags, which is not widely recycled.”

The study included market research and interviews. While this particular study

may not be relevant and repeatable in other places, the findings are rather

disturbing. Thus, I will quote Freedonia Group’s summary of the conclusions of

the study:

“In 2022, following implementation of the New Jersey

bag ban, total bag volumes declined by more than 60% to 894 million bags.

However, the study also shows, following New Jersey’s ban of single-use bags,

the shift from plastic film to alternative bags resulted in a nearly 3x

increase in plastic consumption for bags. At the same time, 6x more woven and

non-woven polypropylene plastic was consumed to produce the reusable bags sold

to consumers as an alternative. Most of these alternative bags are made with non-woven

polypropylene, which is not widely recycled in the United States and does not

typically contain any post-consumer recycled materials. This shift in material

also resulted in a notable environmental impact, with the increased consumption

of polypropylene bags contributing to a 500% increase in greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions compared to non-woven polypropylene bag production in 2015. Notably,

non-woven polypropylene, NWPP, the dominant alternative bag material, consumes

over 15 times more plastic and generates more than five times the amount of GHG

emissions during production per bag than polyethylene plastic bags.”

“The study also found that New Jersey retailers faced

significant changes in their front-end business operations due to the bag ban.

No longer permitted to provide complimentary single-use plastic or paper bags,

retailers are offering alternative bags for sale to fill the void.

Simultaneously, consumers are rapidly transitioning to grocery pickup and

delivery services, which typically requires the use of new alternative bags for

every transaction. As a result, alternative bag sales grew exponentially, and

the shift in bag materials has proven profitable for retailers. An in-depth

cost analysis evaluating New Jersey grocery retailers reveals a typical store

can profit $200,000 per store location from alternative bag sales – for one

major retailer this amounts to an estimated $42 million in profit across all

its bag sales in NJ.”

“Despite retailers finding a compelling business case

for selling alternative bags at a profit, the increased plastic consumption and

GHG emissions generated during alternative bag production hamper retailers’

ability to promote alternative polypropylene bags. FCR’s analysis of New Jersey

bag demand and trade data for alternative bags finds that, on average, an

alternative bag is reused only two to three times before being discarded,

falling short of the recommended reuse rates necessary to mitigate the greenhouse

gas emissions generated during production and address climate change.”

To summarize, in this case, more plastic is being

produced and consumed, the stores are profiting, and more greenhouse gases are

being emitted. While I will reuse my bags quite a lot (way more than the 2-3

times mentioned in the study), I will still use single-use bags where they are

available in other places I shop. That is perhaps the one variable that can

change the results the most. If anything near these results occurs in the very

liberal city (an outlier urban enclave in a very conservative mostly rural region)

where I shop, then the goal here will surely backfire as well. Last I heard the

city was being challenged by the state, who does not want cities to be able to

ban.

Alternatively,

there are many other groups, studies, and websites that say these bans work,

including the ban in New Jersey. Environment

America reports that: “Bans in five states and cities that cover more than

12 million people combined – New Jersey; Vermont; Philadelphia; Portland, Ore.;

and Santa Barbara, Calif. – have cut single-use plastic bag consumption by

about 6 billion bags per year. That’s enough bags to circle the earth 42 times.”

“Adopting a ban on single-use plastic bags that’s similar to those policies

could be expected to eliminate roughly 300 single-use plastic bags per person

per year, on average.” If it is true that a person uses 300 single-use bags

a year and if it is also true that they use the more permanent bags just 3

times on average then that would equate to about 100 bags per year of the

heavier polypropylene bags. I currently have about 15 or 20 of these bags but I

also use paper bags when I forget. I am guessing that I will get through most or

all of a year with the 15-20 bags, but others will likely not. They may rip or

get dirty or perhaps even unsanitary if they carry a lot of food. For instance

I spilled blueberries in one yesterday. Environment America, along with US PIRG

Education Fund and Frontier Group produced a short paper: Plastic Bag Bans

Work which points out that such bans do result in less pollution where they

are enacted. I am sure this is true since the lightweight bags are easily

carried away by the wind while the heavier bags (with more actual plastic in

them) are not. Thus, less local litter is a given. I have been doing Adopt-A-Highway

for the past 25 years so I would probably appreciate that, although where I do

it is not that near the ban area. The study then goes on to acknowledge that

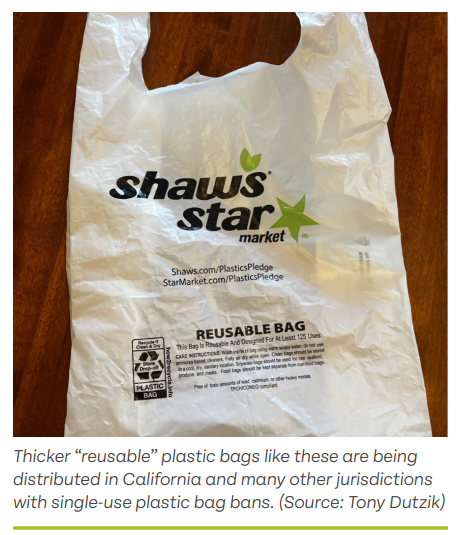

thicker reusable (polyethylene?) plastic bags do result in more plastic bag

waste by weight in a study from California. The picture below shows a plastic

bag that looks like any other plastic bag but is apparently thicker and says on

it that it is reusable. It looks like this bag would blow away in the wind

pretty easily as well.

Source: Plastic Bag Bans Work. Environment America, US PIRG Education Fund, Frontier Group.

The study also notes that while paper bags are recyclable,

people tend to use new ones every time they shop, which means more waste to

deal with for landfills and recycling facilities. They recommend a paper bag

fee. They note that Vermont’s 10 cents per bag fee resulted in a 3.6% increase

in paper bag use but a similar 10-cent fee in Mountain View, California

resulted in a 67% decline in customers using a paper bag. Thus, the post-ban data

can vary quite significantly, and the jury is still out on whether the bag bans

work overall. If local plastic waste reduction is the main goal, then they

probably work well, but if other factors are considered such as overall plastic

production and consumption, and greenhouse gases, then it would appear that

they do not work at all.

In summary it

seems that the benefits of such single-use plastic bag bans are less litter and

visible plastic pollution in the local area of the ban and the downsides of

such bans are more are pollution from more polypropylene plastic production, perhaps

more pollution from increased paper bag production, and increased greenhouse

gases. Essentially, the bag bans are a tradeoff with uncertain net benefits and

net risks but no great benefits and probably no great risks compared to no bans

References:

Blue

state’s bag ban meant to protect environment backfires at staggering rate:

study. Emma Colton. Fox News. January 24, 2024.

Blue state’s bag ban meant to protect

environment backfires at staggering rate: study (msn.com)

Freedonia

Report Finds New Jersey Single-Use Bag Ban Boosts Alternative Bag Production,

Increases Plastic Consumption, and Drives Retailer Profits. Kristen Pieffer. January

9, 2024. Freedonia

Report Finds New Jersey Single-Use Bag Ban Boosts Alternative Bag Production,

Increases Plastic Consumption, and Drives Retailer Profits - The Freedonia

Group

Plastic

Bag Bans Work: Well-designed single-use plastic bag bans reduce waste and

litter. Environment America. U.S. PIRG Education Fund. Frontier Group. January

2024. Plastic

Bag Bans Work (publicinterestnetwork.org)

No comments:

Post a Comment