The daunting challenges of financing decarbonization at

the level required by the more aggressive decarbonization scenarios being

pushed by deep decarbonization and fast decarbonization advocates are quite

sobering. Trillions of dollars per year from the private sector would be

required to achieve those targets. That makes deep and fast decarbonization

less likely in reality. It is really a longshot but in some ways that depends

on how you look at it. Private capital deployment has constraints, and the

number one constraint is financial risk, which must be mitigated to the

satisfaction of the investors. As a business externality decarbonization is

inherently unprofitable, especially at first. It requires government

subsidization and/or the regulatory nudging of a carbon market. As long as public

and support is maintained, and private capital is available there can be

success. However, operating in crisis mode will probably not be helpful.

Cost Estimates

A presenter at

the recent Energy Futures Energy Finance Forum (EF3) live stream revealed that

current private equity per annum for decarbonization is at about $600 billion

and that would have to rise to $3-5 trillion annually to meet decarbonization

targets. The IEA estimates we need $4.4 trillion annually from about $1.4

trillion from all sources now, which means total annual investment must more

than triple to meet targets. Is that reasonable or sustainable? The number in

the billions is already high for inherently unprofitable investments and

increasing it by multiple times times is not going to be helpful to the world

economy, which is already struggling due to inflation and high interest rates. Investors

face many risks and to compel them towards more investments that are low return

at best but more likely little to no return certainly doesn’t seem like a sound

financial strategy. Of course, each project is different and must be evaluated individually.

The government needs to be mindful of vetting projects so that subsidies are

given to projects that can be viable and profitable at some point. Advanced

nuclear and CCS both support lowering the emissions intensity of reliable

non-intermittent energy sources and should perhaps be prioritized. Solar and

wind are best supported by current levels of tax credits and by investments in infrastructure

upgrades. Advanced nuclear is reliant on government subsidization. CCS, hydrogen,

and biofuels are favored by the fossil fuel industry which is a major source of

private capital for these projects as well as government incentives like 45Q.

Emphases

In the EF3

forum Senator Chris Coons emphasized the importance of investment for scaling

up new tech that looks promising, like small modular nuclear reactors, carbon

capture and sequestration, and hydrogen. He also noted the need for permitting

reform in both clean and fossil energy projects and the need for developing

countries to develop their fossil resources as well as clean energy. He also

emphasized the effectiveness of switching from coal to gas. These are all

pretty clear things to prioritize and expedite including stopping the nonsense

of not lending to developing countries for the fossil fuel projects they need

to help their economies, despite the emissions. In developing countries energy

and modern electricity access should trump decarbonization concerns.

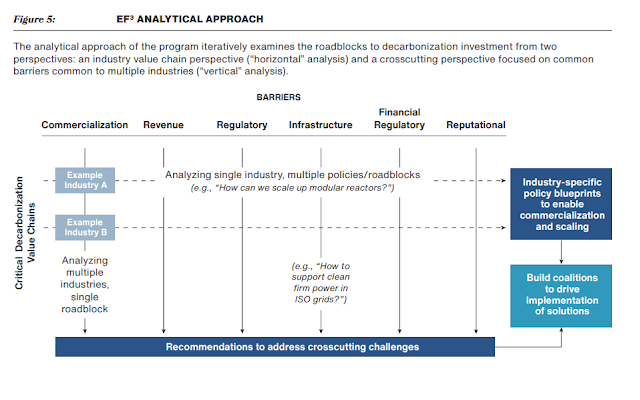

Investment Risk Management

Investors face

several types of risk. There is technology risk, revenue risk, regulatory risk,

infrastructure risk, financial reg risk, reputational risk. The government can

alleviate some of those risks with subsidization, regulatory and permit reform

and streamlining, and longer-term financial backing. The IMF notes that subsidies

must be credible and irreversible. Corporate and institutional investors require

investments that are stable and steady in the longer term, even if returns are

low. All these risks need to be priced. Investors understand the “why” of what

they are doing in decarbonization investment but the “how” is the challenge.

There is a need to be pragmatic and to avoid being overly aspirational with

emissions reduction. We know that early-stage projects often have much higher

costs before scaling can happen, but we still need to concurrently assess costs

as projects are being developed. Former Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz

emphasized the government nudges that are now in place in the U.S. with the infrastructure

bill, the IRA, and the Chips Act. He suggested some goals for 2030 including

bringing projects to “manufacturability” so that scaling and filled “order

books” can bring down prices and increase speed and quality. He said that

demonstrable tech that can be deployed at scale should be a major goal for

2030. That does seem to be the case for both advanced nuclear and CCS. He also

noted that the hard to abate heavy industry sector needs to get moving as well

with government support. He also noted that the investment, tech, and policy communities

all need to be provided with enough information to be able to determine feasibility

of projects. Since there is blended public and private finance, there needs to

be a retuning of information sharing to all parties so that risks can be shared

and understood as best as possible by all parties.

These

different risks need to be evaluated for each technology and at each point

along the value chain of each technology. In order to attract institutional

investors these risks must be thoroughly analyzed, understood, and hedged. Decarbonization

investments are long-term and can be aligned with institutional investment but

only if properly risked. Below is a graph of the perspectives of each class of

investors. One can see that each class is more or less aligned with a different

phase of these energy decarbonization projects.

Energy Futures gives the innovation process itself four

phases: invention, translation, adoption, and diffusion. Between each of these

phases is a “valley of death,” a phrase which shows that there are several

perilous journeys that must be undertaken for each project where risk may kill

the project. This is why announcements of new scientific breakthroughs do not

often end up being new technological breakthroughs.

The third figure below simply shows that each of the

aforementioned risks need to be evaluated and mitigated as potential roadblocks

for each technology I order to get it across those valleys of death.

Climate Investment Exposure to Silicon Valley Bank

Failure

While there

has been quite a lot of blame going around about the Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failure

and now the Signature Bank failure, its hard to pinpoint any specific blame

except to those managing the assets. I’m no finance expert by any means but I

can understand what I read. Progressives are blaming Trump (weakening of

Dodd-Frank in 2018). Conservatives are blaming Biden. Some are blaming the Fed.

Some are blaming woke investment. Some are blaming wealthy investors. However,

it seems that most agree that the banks exhibited poor risk management in light

of prevailing market conditions. Certainly, inflation and the reactionary climbing

interests rates were a factor, but one the bank managers should have been

hedged more against. SVB was involved in clean energy investment as well as

other investments with unpredictable returns involving startups and volatile markets

like cryptocurrencies. Fervo Energy, the company involved in a major DOE funded

geothermal energy research project in Utah, was an SVB customer. No doubt, many

other decarbonization investments were involved as well. SVB lent to a majority

of the community and residential solar projects in the country. Some have

called it a ‘climate bank.’ While solar projects are not considered risky, they

are generally low return and a portfolio full of low return projects is as not well-hedged

as one with high return projects to balance them. Some solar CEOs think that the

bank’s failure will indeed have an impact on the industry going forward but

will sort out eventually as other banks concur that these solar projects are

sound in the long term. Others think they will find other lenders quickly with

little disruption. While demand for solar projects is high, they dropped by 16%

in 2022 for a few reasons: Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, higher interest

rates, and supply chain issues.

Unfortunately,

risky investments can become catastrophic as we have seen with some

cryptocurrency investments and the current bank runs. Decarbonization investments

need not be overly risky but by nature they are low return and often involve

venture capital. Thus, their risk profile is higher than most investments. The

current high inflation/high interest rate environment does not favor a majority

of investments and high risk is amplified in such an environment. This is yet

another among many reasons to tap the brakes on the energy transition. Aggressive

decarbonization pledges and mandates are due for re-tunings for a number of

reasons.

Even though I

have heard deep decarbonization advocates say we can’t afford to slow down

decarbonization, perhaps a better question is can we afford to speed it up? I

would say no, we can’t. Once again, as I have concluded in other articles the near-term

to 2030 decarbonization goals will likely have to be scaled back and they can

be since they are front-end loaded, meaning we can still approach later goals

without adhering to deep emissions cuts in the near term. One might also fault

the 1.5 deg scare with the ICCPs 2018 report as the reason 2030 goals got so

front-end loaded. I read that Greta Thunberg ‘quietly’ deleted a tweet from

2018 where she claimed the world would end in 2023 if we did not aggressively address

climate now. Oops.

Implications of U.S.-China Competition

As noted by Jennifer Lee in the Atlantic

Council’s Energy Source Newsletter, while the Chips Act and other maneuvers to beef

up U.S. domestic production of semiconductor chips, solar panels, lithium, and

other critical minerals, and associated supply chains are no doubt useful in

order to increase energy and tech security, in themselves they do not increase

the rate of decarbonization and will use up a significant portion of funding from

the infrastructure bill and the IRA. These useful spends won’t help us meet

decarbonization targets any faster. China strongly dominates rare earths and

rare earth processing as well as the solar the PV solar supply chain. They also

dominate wind energy supply chains. The expected U.S. restrictions on exports

to China of semiconductor chips is expected to be countered by China with a restriction

on solar panel equipment in a typical tit-for-tat. The reality is that our current

geopolitical tensions with China will hurt both countries, particularly in the

short-term, again leading to a slowing of decarbonization efforts as costs go

up. Another recent row involves the Ford-CATL EV battery deal which involves

Chinese-made lithium iron phosphate battery technology. Elements in both the

U.S. and China are claiming that they are wary about sharing technology. This

kind of suspicion and distrust is not conducive to successful cooperation. Of course,

some competition is healthy, but we need to be careful to avoid creating unnecessary

obstacles between the world’s two biggest carbon emitters.

Big Oil as Integrated Energy Companies Likely to Be

a Big Part of Private Decarbonization Investment

Big oil majors

have long been major investors in alternative energy, being instrumental in the

very development of tech like solar energy and lithium batteries. Now, as some

of the Euro-majors in particular are pivoting to become so-called integrated

energy companies, investment in clean energy is expected to increase in the

coming years. However, there will be bumps in the road. One bump was recently

revealed as BP pulled back their previously ambitious green energy investments.

It could simply be that their enthusiasm was too high and their goals overly

ambitious in the short-term. After the highly profitable 2022 for oil and gas they

perhaps wish they would have waited a bit longer to divert funds away from oil

and gas toward renewables and other green tech. Despite record profits, BP’s

underperformance relative to their peers led their management to scale back

their goals to decrease oil production by 40% by 2030 to a 25% reduction. Thus,

their decarbonization has been decelerated a bit, although they claim their

overall goals and plans for net-zero by 2050 have not changed. BP had increased

their investments in their so-called “transition growth engines” which include

renewables, bioenergy, CCS, hydrogen, and EV charging, from 3% to 30% since

2019. Susannah Streeter, head of money and markets at Hargreaves Lansdown,

noted that BP has two sets of investors to please: those seeking the highest profits

and those seeking responsible investing in clean energy tech. Half of BP’s

largest investors are in the Climate Action 100+ group of activist investors. They

have nudging sway and were not pleased by BP’s pullback. Shareholders approved

BP’s initial planned 40% production increase by 2030 so BP will have to be

careful going forward. In any case, the extreme profitability of 2022 allowed

them to actually increase their investments in those transition growth engines

as well as in more oil and gas production so the shear profitability of oil and

gas is funding both ventures. Indeed, many oil and gas companies are still flush

with cash so that will help with decarbonization capex in the near-term. This

is true of oil and gas companies across the board: majors, independents, and

private equity companies. Fiscal discipline has paid off and geopolitical

forces have added to the bounty. However, weather has not been cooperative for

the natural gas sector at least for the short term. Even so, the outlook is

decent as natural gas and LNG demand is expected to remain high for some time

to come.

Abated vs. Unabated Fossil Fuels

Ministers form

the 27 EU countries agreed on March 9 to focus on phase-out of unabated fossil

fuels at this year’s COP28. They also want the fossil fuel peak to come sooner

and to phase out all unabated fossil fuels well ahead of 2050. I see this as

more rhetoric since it is unlikely China and India are going to heavily pursue

CCS and methane emissions abatement in the near or medium term. Poor developing

countries would be burdened even more to be subjected to abatement. A question

would be what constitutes abated vs unabated. I see it as just another aspirational

statement but also as a nudge. While it may be fine to nudge those that can

financially handle abatement costs like Big Oil companies, the idea of nudging

those less able to fund abatement does not seem fair to me. African countries

have complained about restrictions on acquiring financing for fossil fuel projects.

I see this focus on abatement as an extension of that. I would suggest that they

be excluded from such requirements, with the caveat that they could add

abatements later or be subsidized for those abatements by other countries.

Conclusions

New decarbonized technologies like advanced

nuclear, CCS/CCUS, and hydrogen can be economic or relatively economic under

the right circumstances and with adequate support to get each technology going

towards full commercialization. However, support will need to be maintained and

economics will need to be constantly evaluated in order to fund the best

options optimally. Energy sources providing reliable power should be

prioritized over intermittent sources. Options like blue hydrogen should be

favored over green hydrogen where applicable, such as where natural gas is

abundant and cheap. The EF3 report acknowledges that profitability will take

time as first-of-a-kind projects will cost more, next-of-a-kind projects

somewhat less, and nth-of-a-kind projects will begin to gain financial

advantages. But Moniz’s admonition still stands – we need to demonstrate by

2030 that these projects can be deployed at scale.

References:

Increasing

the Quality of Investments for Deep Decarbonization. Energy Futures Finance

Forum. February 2023. EF3-Framing-the-Energy-Futures-Finance-Forum-1.pdf

Energy

Futures Finance Forum: Increasing Clean Energy Investment Quality: Live Stream

February 28, 2023.

Solar companies

offer reassurance after renewables financier Silicon Valley Bank collapses.

Diana DiGangi. Utility Dive. March 14, 2023. Solar

companies offer reassurance after renewables financier Silicon Valley Bank

collapses | Utility Dive

BP’s

green energy dilemma: investor confidence goes both ways. William Farrington. Proactive.

March 6, 2023. BP’s

green energy dilemma: investor confidence goes both ways

(proactiveinvestors.com)

Beauty

and the beast: Implications of the US-China tech war on climate and energy.

Jennifer Lee. Atlantic Council. EnergySource. March 6, 2023. Beauty

and the beast: Implications of the US-China tech war on climate and energy -

Atlantic Council

EU

agrees to push for global fossil fuel phase-out ahead of COP28.

EURACTIV/Reuters. March 10, 2023. EU

agrees to push for global fossil fuel phase-out ahead of COP28 – EURACTIV.com

No comments:

Post a Comment